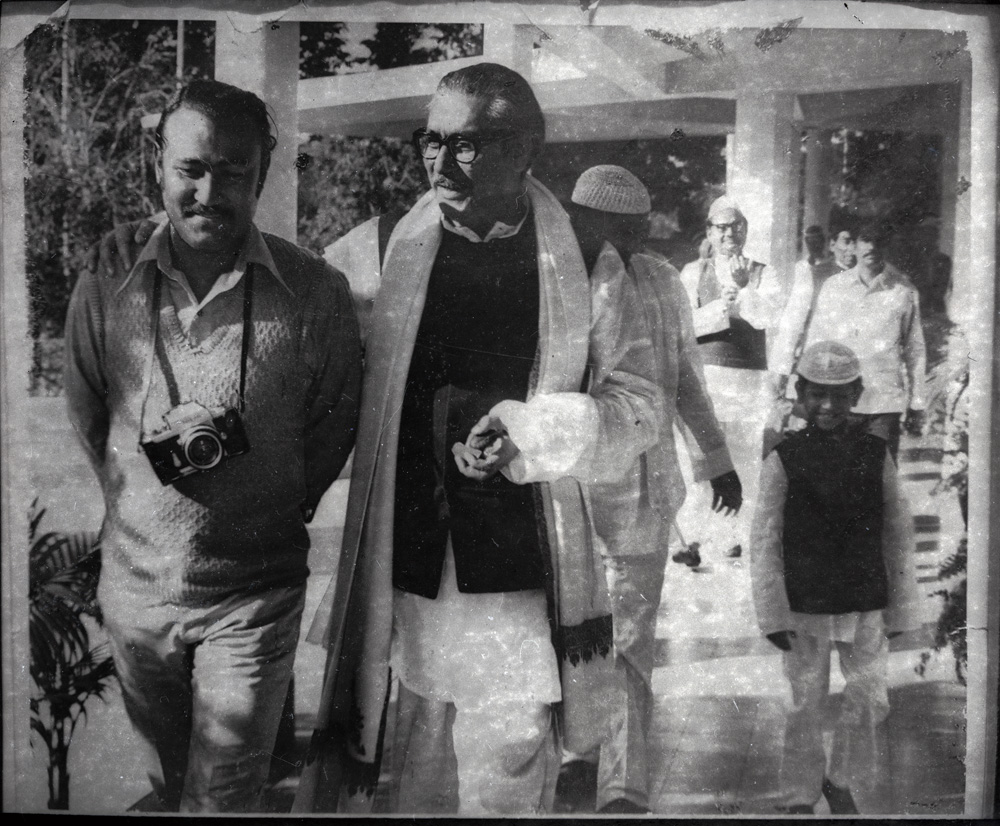

Looking at this photograph, one of the few in our library where the photographer is unknown, I realise how times have changed. This is the undisputed leader of a country with his arms across the shoulder of a newspaper photographer not known for being affiliated to his party.

No security guards, no party goons, no chamchas. Both men are at ease with the situation. The smiles, the casual gait, Rashid Bhai with his camera dangling, a single prime lens. Not even a camera bag (and this was the time of film when you only had 36 exposures). How times have changed. Sure, we live in a more security conscious world, but the distance between the leaders of today, and the people, isn’t simply about changed situations, it is about changed attitudes. Today the proximity between leaders and the people surrounding them has much more to do with business and benefits, than with humility and largesse. There was much more give and much less take.

Rashid Bhai was doing poorly and I was keen that the incredible history this talented photographer had documented over the years should not be lost. Initially we commissioned Momena Jalil and Moinul Hassan Tapu to get the information associated with the photographs, mostly kept in a large plastic bag in Rashid Bhai’s house. Tapu sat at Rashid Bhai’s bedside and meticulously wrote down what he could salvage from the photographer’s fading memory. Rashid Bhai was slipping away, and rather than tax him further with what was for him becoming a laborious task, we decided to scan the key photographs, project them and have him talk over them.

Even with this failing health, Rashid Bhai was still the master storyteller. His ready wit, candour and inimitable charm surfaced throughout the ‘interview’. One of the stories he said that day said a lot about the friendship that these two men shared.

It was the wedding of Sheikh Kamal (Bangabandhu’s son). Rashid Bhai was going about doing his paparazzi stuff. Like any other mother at her son’s wedding day, Begum Mujib was trying to bring some sort of order into the chaos. The paparazzi got in the way and the mother told him off. This was when the Bangali trait of Rashid Bhai surfaced. He was miffed, and decided he would not join the wedding dinner. Word got to Bangabandhu and he came to appease him, but the photographer would not relent. He was hurt and that was that. It was pure obhiman, a Bangla word difficult to translate. A hurt that only someone you are especially close to can cause. This had nothing to do with the status of a head of state, or his wife, or a photographer going about his job. It was maan/obhiman and all about relationships.

No less a Bangali Mujib responded: tahole ami o khabo na. tui ki chaish amar cheler biyete ami na khai? OK, so I too won’t eat. Is that what you want, that I not eat at my son’s wedding? Rashid Bhai relented. Food was brought. The two men sat side by side and ate. The use of the word ‘tui’ which Mujib often used, is one of extreme familiarity with multiple connotations. It can denote status, hierarchy and familiarity, and shifts with situations. Mujib was famous for the way he used it. Seamlessly switching between tui, tumi and apni as needed, and with marvellous ease.

It was this trait of the man that we have forgotten. Mujib was a great leader and a great politician. Like many revolutionaries who became statesmen, he too made mistakes. Some significant. In the end, he was a man, with human triumphs and failings. In our polarized political environment, we have either deified or demonised the leader and the man has never been able to surface. His humility, his closeness with the people, his ability to be ordinary, was perhaps his greatest strength. A strength we have not recognised and certainly not emulated.

I have noticed this in other great leaders. Nelson Mandela had once changed the date of a photo shoot, because I had not been able to arrive in time to Johannesburg. It was a long trip from Mexico City and on the 8th of July 2009, when I was meant to have been at his home in Jo’burg, I was still stuck in Dubai. Photographer friends have told me of how he cut short his speech, so the photographers standing in the rain could get to dry shelter. Stories of Mujib, taking time off from important meetings because a child wanted to meet him, is legendary. In the complex political quagmires they operated in, these great men have sometimes stumbled. We need to recognise the slips, analyse the reasons and learn from the mistakes, so they are never repeated. In the end it is their humanity that will surface. That remains their endearing trait.

The statesman and the photographer were both at the pinnacle of their craft. They were also great friends and fine human beings, each having an abiding respect for the other. The latter trait we seem to have forgotten.

Shahidul Alam is a photographer and social activist. He is the founder of Drik.